Relief from Pain in the Neck

Interpretation and Recommendations for incomprehensible CT Scan Pathology report for Neck Pain. A new service we are providing.

Not understanding something is a pain in the neck.

The emergence of the World Wide Web, now known as the internet, in 1989 was comparable to the industrial revolution around the 1800s via significant technological advancements that fundamentally changed how people worked, communicated, and lived. In 2025 another significant technological advancement is afoot. Described colloquially as Ai, in essence it is the sudden laser like focus of the largest almost infinitely resourced companies in the world to develop automation and an information retrieval system that communicates with language like humans and is accessible to every human on earth.

Of course rapid advancements demand precaution due to possible unforeseen consequences. However, by the end of 2025, there will not be an aspect of human work and creative activity that is not enhanced or integrated with some aspect of Ai.

At the same time one can see that many systems and structures that largely emerged out of the industrial revolution like public health, medicine, researching science, education and economic equity have grown tired, unsustainable, unaffordable, unavailable to many and indeed lacking in public trust.

One hope of the Ai revolution is to once again level the playing field, in part through access to learning or simply just wanting to know, being curious that is independent of organisations and institutions, marketing and eventually, bias. It’s a hope at this stage.

My chosen field of expertise is human health. Most assuredly an area where Ai is rapidly advancing and integrating. This article and others listed below, is an example of a service we are now providing that assists people. Indeed, takes the pain out of having to deal with unknown causes and outcomes of health issues and more importantly, what to do about it, at least in the short term while you find an ethical wholistic medical/health professional who will try to figure it out with you or at least, fit you in.

Our service is centred around being informed and learning about the aetiology (an investigation of the cause or reason for something) of our mental and physical health issues. This approach considers our behaviours, habits and misconceptions that are contributing to pain, discomfort and stress. AND, how to respond to our immediate concerns and long term health while leaving medication and surgery as an absolute last resort! See more about how you benefit from this approach and how we take immediate action in our previous article Ear issues with scary Lab result.

These examples or case studies, if you wish, show…

Having strange symptoms with unknown cause and working up a differential diagnosis - which is in essence an investigation that sequentially and methodically eliminates the usual suspects and gives short term recommendations that alleviate pain, stress and angst. See Double Vision. An example of learning to learn when health gets personal

Having pathology scans like X-rays, CT scan or MRI imaging results without an explanation or report, which can sometimes take weeks or even longer. Getting these images interpreted immediately through our service. See Turning Pain into Gain through Learning

Having a pathologist report for imaging or scans and having no idea what it is saying and being unable to get to see a doctor for long enough to have it explained or who to see to follow-up. This article is an example of this. The client expressed really understanding details and learning along the way - meaning this is a long article.

Having a blood test result that looks ominous or indeed of unknown long-term consequence and not sure what it means or what to do while being unable to get to see a doctor for long enough to have it explained or who to see to follow-up. See Ear issues with scary Lab result

Situations where a symptom or blood test result is difficult to act upon with clarity right away because of the complexity and interconnected bodily systems involved (Thyroid issues in this particular case). This case is currently in progress.

More to come.

Make no mistake - this is not about replacing doctors or allied health professionals. Rather it is about being as informed as you can and when the times comes, being able to collaborate with these professionals so as to come to long term solutions, request further investigations or discuss other interventions.

Our service fills a gap in the prevailing system that is struggling to keep up with demand, mostly by providing targeted opportunities to learn about your specific situation and act upon it as appropriate and with clear precautions. Immediately.

Here we provide a de-identified CT scan Pathology report that the client had little time to speak with his doctor about. The client expressed really understanding details and learning along the way - hence this is a long article.

Contents

Original CT Cervical Spine Report Summary

Understanding the Findings

What These Results Mean for Your Recovery

Precautions and Tips for Physical Activity and Rest

Expected Recovery Timeline

Gentle Exercises and Movements to Support Recovery

What is a CT scan, and How Does it Compare to an MRI?

Glossary of Technical Terms

Taking advantage and using of our new service

Original Pathologist Report of Neck CT scan

April 2025

Original Pathologist Report

Visit Date: 07 Apr 2025

Examination: CT Cervical Spine

Clinical Notes:

Hyperextension injury. Neck pain radiating to jaw and face ? fracture ? disc impingement.

Findings:

• Straightening of the cervical alignment.

• No vertebral compression fracture or aggressive osseous lesion.

• Spondylosis, with posterior and bilateral uncovertebral disc-osteophyte complexes at many levels.

• Mild diffuse facet joint degenerative change.

Level-Specific Observations:

• C2/3: No significant canal or neural exit foraminal stenosis.

• C3/4: Mild left neural exit foraminal stenosis, but no definite nerve root compression.

• C4/5: Mild canal stenosis. Severe left neural exit foraminal stenosis with probable compression of the exiting left C5 nerve root.

• C5/6: Mild canal stenosis. Severe left neural exit foraminal stenosis and moderate right neural exit foraminal stenosis, with probable compression of the exiting left C6 nerve root.

• C6/7: No significant canal stenosis. Severe left neural exit foraminal stenosis, with probable compression of the exiting left C7 nerve root.

• C7/T1 to T1/2: Normal.

• Lung apices are clear.

Conclusion:

• No definite acute traumatic injury identified.

• Cervical spondylosis with probable compression of the exiting left C5, C6, and C7 nerve roots in the neural exit foramina.

Detailed Interpretations and Recommendations for CT Cervical Scan Pathologist Report

Original CT Cervical Spine Report Summary

Concurrent symptoms of the client

The client went swimming recently and put his head under a very powerful waterfall and since has had neck pain. Person is healthy and 65 years and does a lot of physical work now and then. No prior treatment or diagnosis for neck or spine issues but has had collar bone issues from accident in his 20's. Current symptoms include sore neck and shoulder with right side pain extending up to behind his ear nearly every day. Most days has headaches. After doing overhead work like looking up pain can be worse. Generally, pain is getting worse since the accident about a month ago.

Findings: No acute fracture or dislocation is identified. There are multilevel degenerative changes in the cervical spine. At C4-5, a mild posterior disc osteophyte complex is present with mild central canal stenosis and mild bilateral neural foraminal narrowing. At C5-6, a moderate-sized posterior disc osteophyte complex causes moderate right neural foraminal stenosis and mild central canal stenosis; the left neural foramen is mildly narrowed. At C6-7, a small posterior disc osteophyte complex causes mild-to-moderate bilateral neural foraminal stenosis (right greater than left), without significant spinal canal stenosis. The cervical spinal cord is normal in caliber. No prevertebral soft tissue swelling. The remaining cervical levels are unremarkable.

Impression: Multilevel cervical spondylosis (degenerative changes), most pronounced at C5-6 and C6-7 with moderate right-sided foraminal narrowing at C5-6. No acute bony injury identified.

Understanding the Findings

Let’s break down what all that means in simple terms and explain each finding one by one. First, some background:

Figure: Side view of the neck (cervical spine) with the seven cervical vertebrae (C1–C7) highlighted in red. The cervical spine consists of 7 stacked bones in the neck that protect the spinal cord and support the head. They are numbered from C1 at the top (just below the skull) to C7 at the bottom (at the base of the neck).

No Acute Fracture or Dislocation

The report says “No acute fracture or dislocation is identified.” This is good news. It means that the CT scan did not show any broken bones in your neck or any bones out of alignment. In other words, the recent waterfall incident did not cause any major break or sudden misalignment in your cervical spine. Your vertebrae (the neck bones) are all in their normal positions and intact, which is reassuring.

Fracture: a break in a bone. “No fracture” means none of the neck bones are broken.

Dislocation: when a bone is out of place at a joint. “No dislocation” means all joints between the neck bones are normally aligned.

This finding indicates that, structurally, your neck bones handled the injury without any cracks or slips. So the source of your pain is likely due to softer tissue injury (like muscle strain) and wear-and-tear changes rather than a sudden bone break. That’s a positive sign for your recovery, because fractures or dislocations would require more urgent interventions.

Multilevel Degenerative Changes (Cervical Spondylosis)

The report notes “multilevel degenerative changes in the cervical spine.” Degenerative changes refer to wear and tear in the spine that has occurred gradually over time. Another term for this is cervical spondylosis, which simply means age-related arthritis or degeneration in the neck.

Being 65 and otherwise healthy with no prior neck issues, it’s common to have some of these mild degenerative changes even if you’ve never had symptoms before. Over decades, the discs and joints in our necks naturally dry out and develop small bone spurs (tiny bony growths) from everyday use procaremedcenter.com. Think of it like how our skin gets wrinkles with age – our spine gets a bit of “wear and tear” too.

Multilevel means these changes are seen at several levels of your cervical spine (not just one spot). In your case, the scan found changes at C4-5, C5-6, and C6-7 (which are the discs and joints in the lower middle part of your neck). These changes can include things like:

Disc degeneration: The cushions between vertebrae (intervertebral discs) become thinner or bulge a little.

Osteophytes: Small bony projections (bone spurs) form on the edges of the vertebrae or joints due to arthritis.

Facet joint arthritis: The small joints in the back of the spine (facet joints) may show arthritic changes.

All of these fall under “degenerative changes.” They happen slowly and are very common as people age – most people over 60 have some degree of cervical spondylosis, often without any pain. However, in some cases (like yours), a sudden activity or injury can irritate these areas and cause symptoms. The waterfall incident likely aggravated these pre-existing mild changes, making them symptomatic (causing pain) even though you hadn’t noticed any neck issues before.

Key point: Degenerative = chronic wear-and-tear changes, not a sudden injury. It doesn’t mean your neck is “falling apart” – it means there are age-appropriate changes like mild arthritis. These can be managed and often don’t progress rapidly. Now let’s look at the specific levels mentioned:

C4-5: Mild Disc Osteophyte Complex with Mild Stenosis

At the level between the 4th and 5th cervical vertebrae (C4-5), the report says: “mild posterior disc osteophyte complex with mild central canal stenosis and mild bilateral neural foraminal narrowing.”

That’s a lot of technical words! Here’s the translation:

Posterior disc osteophyte complex: This phrase means there is a combination of a bulging disc and small bone spurs at the back side of the disc. The disc between C4 and C5 has likely bulged a tiny bit and the edges of the vertebra have little bone spur growths. Together, the disc bulge + spur is called a “disc osteophyte complex.” It’s basically a slight protrusion into the spinal canal or nerve openings, made of disc material and bone spur. “Posterior” just means towards the back (which is where these bulges usually happen, toward the spinal canal).

Mild central canal stenosis: The “central canal” is the hollow tunnel in the middle of the vertebrae through which the spinal cord passes. Stenosis means narrowing en.wikipedia.org. So “central canal stenosis” indicates the spinal canal at C4-5 is a bit narrowed. Mild stenosis means the narrowing is small – there is no severe pressure on the spinal cord, just a slight tightening of space. In your case, it’s mild enough that the cord is not compressed; the report even notes the spinal cord is normal in size (caliber). So, at C4-5, the canal is a little narrower than normal, but not enough to pinch the spinal cord.

Mild bilateral neural foraminal narrowing: Neural foramina (singular: foramen) are the openings on each side of the spine through which the nerve roots exit from the spinal cord to go to the rest of the body. “Bilateral” means both the left and right side openings are affected. Narrowing of these openings is called foraminal stenosis – basically the little holes where the nerves pass are a bit tighter than they should be my.clevelandclinic.org. In your report, it’s mild on both sides at C4-5. This likely comes from those small bone spurs or disc bulge encroaching on the edges of the holes. Mild narrowing means the nerves that pass through are probably not pinched significantly, but the space is somewhat reduced.

In plain language: At C4-5, you have a bit of arthritis and a slight bulging of the disc with small bone spurs, which is causing a small narrowing of both the spinal canal and the nerve exit holes at that level. It’s mild – so it’s more of a subtle change, not a big compression. This might not be the main source of your symptoms; it’s an incidental age-related finding, but it’s good to be aware of it.

C5-6: Moderate Disc Osteophyte Complex, Moderate Right Foraminal Stenosis

At C5-6 (between the 5th and 6th cervical vertebrae), the report says: “a moderate-sized posterior disc osteophyte complex causes moderate right neural foraminal stenosis and mild central canal stenosis; the left neural foramen is mildly narrowed.”

This is similar to C4-5, but a bit more pronounced, especially on the right side. Here’s what it means:

Moderate-sized disc osteophyte complex: The disc bulge and bone spur formation at C5-6 is a bit larger than at C4-5 – they call it “moderate-sized.” So the wear-and-tear is a little more advanced at this level. It’s still a bulge and bony spur pressing backward.

Moderate right neural foraminal stenosis: On the right side, the foramen (nerve exit passage) is moderately narrowed. This suggests that the nerve root exiting at C5-6 on the right (which would be the C6 nerve root, since in the cervical spine the nerve is usually numbered one higher than the vertebra below) is likely being pinched or compressed to some degree by the bulging disc or spur. “Moderate” stenosis is a middle level – not minimal, but not severe either. It means there is a decent chance this narrowing is affecting the nerve. This correlates with your symptoms: you have right-sided neck and shoulder pain radiating toward the head. The C5-6 level (which affects the C6 nerve root) can cause pain that radiates into the shoulder, shoulder blade, and even up into the neck/head region. Compression of a cervical nerve root is often called a “pinched nerve” or cervical radiculopathy when it causes symptoms like arm/shoulder pain, numbness, or tingling.

Mild central canal stenosis: Similar to C4-5, the main spinal canal at C5-6 is a bit narrowed, but only mildly. So there’s no significant pressure on the spinal cord itself, just a slight reduction in space.

Left neural foramen mildly narrowed: On the left side at C5-6, the foramen is a little narrow, but only mildly. So the left nerve root has some space reduction, but likely not enough to cause issues. You haven’t reported left-sided symptoms, which fits with only mild narrowing on that side.

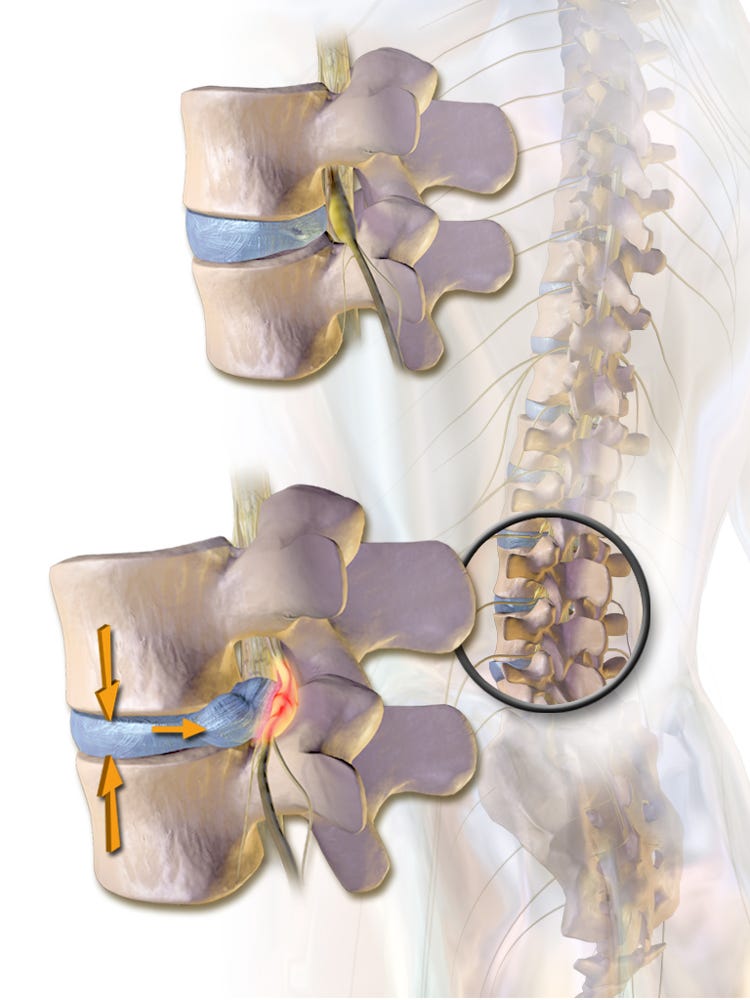

Figure: Illustration of a disc bulge pressing on a nerve root (a common cause of foraminal stenosis and “pinched nerve”). In the top image, the disc is normal. In the bottom image, a bulging disc (blue) and a small bone spur press on the nearby nerve root (yellow), shown by the red area indicating irritation. At C5-6, a similar process is happening – a bulging disc and bone spurs are narrowing the exit tunnel on the right side, which may irritate the nerve root that travels through that space.

In everyday terms, at C5-6 you have a moderate “pinch” of the nerve on the right side due to the arthritis and bulging disc there. This is likely the most important finding relating to your pain. A pinched nerve in the C5-6 region (affecting the C6 nerve) can cause:

Neck pain,

Pain that radiates to the shoulder and down the arm,

Pain that can radiate up into the head behind the ear (because some upper cervical nerve irritation can cause headaches, known as cervicogenic headaches).

It can also sometimes cause numbness or tingling down the arm into the thumb/index finger. (You haven’t mentioned numbness, which is good, but it’s a possible symptom of that nerve root compression.) The fact you have daily headaches and pain behind the ear on the right side may well be linked to this nerve irritation at C5-6 or possibly involvement of the C2/C3 region (upper neck joints) due to overall neck strain. But C5-6 is a prime suspect for the shoulder pain and for pain with looking up.

Because this narrowing is moderate, it means the nerve is likely pressed when you move your neck in certain ways (for example, looking up (neck extension) tends to close down the foramina further, which might explain why your pain worsens with overhead activities or looking upward). The good news is that it’s not severe stenosis – in many cases, moderate foraminal stenosis can be managed with conservative treatments (like physical therapy, rest, and possibly injections if needed) and doesn’t always require surgery. We’ll talk more about management and recovery shortly.

C6-7: Mild-to-Moderate Foraminal Stenosis, No Significant Canal Stenosis

At C6-7 (between the 6th and 7th cervical vertebrae), the report says: “a small posterior disc osteophyte complex causes mild-to-moderate bilateral neural foraminal stenosis (right greater than left), without significant spinal canal stenosis.”

Breaking that down:

Small disc osteophyte complex: The disc bulge and bone spur at C6-7 is small – so there is a little bump, but not very large.

Mild-to-moderate bilateral foraminal stenosis: The openings for the nerves on both sides are narrowed to a mild or moderate degree. It notes “right greater than left,” meaning the right side is a bit more narrowed than the left, but both have some narrowing. So the nerve roots that exit at C6-7 (which would be the C7 nerve roots) have a reduced space, especially on the right side. This is probably another effect of general wear-and-tear.

No significant spinal canal stenosis: The main canal for the spinal cord at C6-7 is adequately open – there’s no noteworthy narrowing of the central canal here. The spinal cord has enough room at this level.

In simpler terms, at C6-7 you have mild arthritis changes causing slight narrowing of the nerve passages on both sides (again a bit more on the right). This is another common spot for degenerative changes. The right side might be adding a little to your symptoms (perhaps some additional right shoulder/arm discomfort), though the main issue still seems to be the C5-6 level above. The C7 nerve, if pinched, can cause pain that radiates down the back of the shoulder or into the arm/hand (especially middle finger). It doesn’t sound like you have strong symptoms of that, which makes sense since the stenosis here is only mild-to-moderate.

Overall, C5-6 is the worst level, with moderate right foraminal stenosis, and C4-5 and C6-7 have milder changes. All these levels together are what the report calls “multilevel degenerative changes.” They collectively contribute to your neck pain picture, but the C5-6 level is likely the chief culprit for the nerve-related pain.

Spinal Cord and Other Structures

The report states: “The cervical spinal cord is normal in caliber.” This means your spinal cord (the bundle of nerves running down the spinal canal) is not being compressed or squeezed. It appears normal thickness. In some severe cases of stenosis, the cord can get pinched, which can cause serious symptoms like weakness, balance issues, or changes in sensation in the arms/legs. You do not have that problem – your cord has plenty of room. The narrowing we discussed is either mild or off to the side (around nerve roots), not hitting the cord itself. So there are no signs of myelopathy (spinal cord compression) on your CT, which is very reassuring.

“No prevertebral soft tissue swelling” means there’s no unusual swelling in the soft tissues in front of the spine (which can sometimes indicate trauma or injury). So again, no sign of any traumatic damage from the incident.

“The remaining cervical levels are unremarkable” – this just means everything else in the cervical spine (like C3-4, C7-T1, and the very top C1-2 area) looked normal with no significant findings. Your old collarbone injury from decades ago is not mentioned, which implies it’s not visible or relevant on this scan (CT of the spine might not even show the distant collarbone well, but in any case, there’s no effect of that old injury on your spine now).

To summarize the findings in plain language: You have age-related changes in your neck (mild arthritis, small disc bulges, and bone spurs) at a few levels, especially C5-6. The injury under the waterfall did not break anything, but it likely aggravated these existing changes, leading to a pinched nerve on the right side of your neck. This pinched nerve is probably causing your right-sided neck, shoulder, and head pain. The term for these findings is cervical spondylosis with radiculopathy (meaning arthritis in the neck with nerve root irritation). Importantly, the scan shows no serious structural damage – the issues are real but moderate, and they can often be treated with conservative measures.

What These Results Mean for Your Recovery

Overall, the CT results are reassuring in that they found no acute injury and only moderate-level changes. Here’s what this means for you moving forward:

Healing is likely with time and care: The fact that there’s no fracture or severe compression is good. Your pain is coming from soft tissue strain and nerve irritation. The body can often heal or adapt from these kinds of injuries over weeks to months. With proper rest, therapy, and modifications to your activities, you should see improvement. In fact, many cases of cervical radiculopathy (pinched nerve in the neck) resolve on their own within about 8–12 weeks for over 85% of people my.clevelandclinic.org. Every person is different, but it’s reasonable to expect significant improvement in a couple of months, with gradual relief starting sooner (often in a few weeks).

Conservative treatment first: Because your spinal cord is fine and the nerve pressure is moderate, doctors will usually treat this without surgery initially. This might include:

Medications: such as anti-inflammatories or pain relievers to manage pain and reduce inflammation.

Physical Therapy: exercises and traction techniques to relieve pressure on the nerve, strengthen neck muscles, and improve posture.

Activity modification: avoiding the motions that worsen your pain (more on that below in precautions).

Possibly heat, gentle massage, or other modalities to ease muscle tension.

If pain is severe or persistent, sometimes epidural steroid injections near the nerve can reduce inflammation.

Surgery is generally a last resort for cases that don’t improve with the above or if there were severe compression (which you don’t have right now).

Expect ups and downs: Nerve pain can fluctuate. Some days might be better, others a bit worse, depending on your activities. Don’t be discouraged by the bad days. Overall, the trend should be toward improvement. The headaches and neck pain should gradually lessen as the inflammation around the nerve settles. It might take several weeks to truly notice it easing. A realistic ballpark: some relief in a few weeks, major improvement by about 2–3 months, and possibly near full recovery by around 3–4 months. In some people it can take up to 6 months for nerve irritation to fully calm down, but you should be feeling much better well before then. The degenerative changes (arthritis) will still be there (they don’t “heal” per se, like a cut would), but your symptoms can resolve as your body adapts and the acute inflammation goes away.

Lifestyle and posture matter: Since you have some general wear-and-tear in the neck, long-term, it will help to maintain good neck posture and keep the neck muscles strong. This can prevent flare-ups. Once you’re past the acute pain, regular gentle neck exercises (as guided by a professional) and being mindful of ergonomics (like your desk setup, how you look at phone, etc.) will be beneficial to keep your neck healthy.

Think of your spine like a car that’s a bit older – it’s got a few dings (arthritis) but it’s still running. You just have to maintain it well and not push it too hard on bumpy roads for a while. With the right care, it should serve you well for years to come.

Next, let’s discuss precautions and daily habit changes to help you recover faster and prevent aggravating your neck.

Precautions and Tips for Physical Activity and Rest

Given your scan findings and symptoms, here are some plain-language precautions and suggestions for activities, posture, and sleep. These will help avoid worsening your pain and aid recovery:

Avoid Overhead and Prolonged “Looking Up” Movements: You’ve noticed pain worsens when you tilt your head back (looking up), such as during overhead activities. This position further narrows the foramina (the nerve passageways) and can squeeze the irritated nerve more. Try to minimize tasks like reaching up high, painting a ceiling, or even prolonged looking up at a high shelf or monitor. If you must do something above shoulder level, take frequent breaks, and try not to crane your neck back more than necessary. For now, keep most activities at or below eye level. If you need to look up (say, to watch birds or something), do it briefly and gently. Repetitive or sustained neck extension (looking up) can increase symptoms of cervical stenosis procaremedcenter.com, so it’s best to limit that until you’re healed.

Be Mindful of Neck Position (No Sudden Twists or Extreme Bends): Avoid quick, jerky motions of the neck. For example, don’t snap your head to look over your shoulder too quickly. When turning to look to the side or behind you, rotate your body rather than whipping your neck around. Also avoid extreme bending of the neck forward or sideways. Gentle movement is good; extreme movement is not. Think “smooth and in mid-range” for neck motions. This gives the nerve a calmer environment.

Limit Heavy Lifting, Especially Over Shoulder Height: Temporarily refrain from heavy lifting or carrying, especially if it involves raising objects overhead. Lifting heavy weight puts strain on your neck and shoulder muscles which can aggravate your pain. If you must lift something, keep it light and keep the object close to your body (e.g., carry groceries at waist level, not with arms extended). For now, also avoid exercises like overhead presses or pull-ups in the gym, as these extend the neck and strain the area. As you heal, you can gradually reintroduce normal lifting with proper form, but ease back into it with guidance.

Maintain Good Posture (especially during computer or phone use): Slouching or hunching forward can put extra pressure on the discs and nerves in your neck. Try to keep your head in a neutral position – ears over shoulders. When using a smartphone or reading, avoid looking straight down for long periods (which is hard on the neck). Instead, lift the material or your screen closer to eye level. If you work at a computer, ensure the monitor is at eye height so you’re not looking up or down too much. Good posture helps keep your spinal spaces open and reduces nerve irritation procaremedcenter.comprocaremedcenter.com.

Take Frequent Breaks from One Position: Whether you’re sitting at a desk, driving, or watching TV, try not to stay in one static position for too long. Prolonged sitting can stiffen the neck and exacerbate nerve compression. Every 30 minutes or so, gently roll your shoulders, turn your head side to side (within a comfortable range), or stand up and move a bit. This prevents any one part of your neck from taking too much sustained pressure.

Use Proper Neck Support When Sleeping: Sleeping posture is crucial because you spend many hours in it. The goal is to keep your neck in a neutral, supported position. Avoid sleeping on your stomach, as that forces your neck to twist sharply to the side and can strain your neck health.harvard.edu The best positions for your neck are on your back or side health.harvard.edu. When on your back, use a pillow that supports the natural curve of your neck – not too high under your head. You might consider a specialized cervical pillow or simply a rolled towel inside your pillowcase to support the neck curve. When on your side, use a pillow that’s higher under your neck than under your head, filling the space between shoulder and neck health.harvard.edu, so your neck isn’t bending sideways. Ensure your head isn’t propped up too much or sagging down. You mentioned headaches; sometimes a poorly supported neck during sleep can trigger morning headaches. So finding a comfortable pillow that keeps your neck aligned could help reduce those. Many people find a memory foam pillow or a feather pillow that they can mold works well health.harvard.edu – the key is comfort and neutral alignment. Also, if lying flat is very uncomfortable due to pain, some people temporarily find sleeping in a recliner or with an extra pillow (semi-reclined position) helps – do what feels best for you.

Heat for Muscle Relief: Consider using a warm pack or hot shower on your neck and shoulder, especially before doing gentle stretches or at the end of the day. Heat can relax tight muscles and improve blood flow, which may ease your discomfort and headaches. Just ensure it’s warm, not scalding, and limit sessions to ~15-20 minutes. If swelling were an issue (usually early after injury), ice would be recommended, but since this is more ongoing stiffness and nerve pain, many people with cervical spondylosis prefer heat or alternate heat/ice.

Listen to Your Body: The pain is actually a useful guide right now. It will usually tell you which motions or activities are aggravating things – respect that signal. If something increases your neck or arm pain significantly, ease off or modify that activity. Pain that is mild and improving is okay to work through gently, but don’t push through severe pain thinking you’ll “toughen up.” Healing nerves can be irritable, and pushing too hard can set you back. On the flip side, if an activity doesn’t cause pain, you don’t have to be afraid of it – movement is good for recovery. It’s all about moderate, controlled activity.

Expected Recovery Timeline

Every individual heals at their own pace, but here’s a general idea of what to expect:

Short term (Days 1–14): In the first couple of weeks after the injury and as you start precautions/therapy, you might still have quite a bit of pain. Don’t be discouraged – nerve irritation can be stubborn. Aim for gradual improvement. You might notice that the intense flare-ups become a bit less frequent or that your baseline pain slowly starts to ease, especially with rest and medication. Headaches might still occur daily initially, but monitor if their intensity or duration is reducing.

Weeks 3–6: By 3 to 6 weeks out, many people start seeing more noticeable improvements. The constant pain often diminishes to intermittent pain. Perhaps your headaches occur less often, or you can do a bit more activity before pain sets in. According to spine specialists, a majority of pinched nerve cases begin to feel better in this window as inflammation subsides and as therapy exercises kick in. You may still have stiffness or some residual aches, but the goal is that you’re more functional than before.

Weeks 8–12 (2–3 months): Around two to three months after, a large percentage of people have significant relief or even resolution of symptoms my.clevelandclinic.org. You may find that you’re mostly pain-free doing everyday activities, with only occasional twinges if you overdo it. The nerve can take time to fully calm down, so even if you feel mostly better, continue with good habits and any maintenance exercises given by your physiotherapist. At this stage, if you’re improving well, likely no further invasive treatment will be needed.

Beyond 3 months: If by 3 months you still have considerable pain or any new symptoms (like weakness or numbness in your arm, which we hope you won’t get), your doctor might consider additional investigations (for example, an MRI, which we’ll discuss soon) or treatments. However, in the majority of cases, by this time people are on the mend or only have mild lingering symptoms. Some very mild symptoms (like a bit of neck stiffness in the morning, or an occasional light headache) might linger simply due to the underlying arthritis, but these can often be managed with exercise and posture long-term.

Full recovery vs. management: It’s possible you’ll get to a point where you feel fully back to normal – no pain, full motion. That is our hope. But it’s also possible you’ll feel “mostly better” with just some manageable discomfort now and then. Given the degenerative changes, think of it like managing a chronic condition: even when you’re pain-free, you’ll want to continue the exercises and precautions as prevention. It’s akin to how someone with a sensitive lower back learns to lift properly even when they’re not in pain, to avoid re-injury. With time, these protective habits become second nature.

If at any point your symptoms significantly worsen – for instance, if you develop weakness in your arm (like you can’t lift your arm or hold objects), numbness that is worsening, or any issues with walking or balance (which would hint at spinal cord issues), notify your doctor immediately. Those are not typical in your scenario and likely won’t happen, but it’s worth knowing the red flags.

Based on your CT, such serious developments are unlikely. We expect a steady recovery. Patience is key: nerve irritation improves gradually. Celebrate small improvements (like a day with less pain, or being able to sleep better) because they signal you’re on the right track.

Gentle Exercises and Movements to Support Recovery

Motion is lotion for the spine – gentle movement can help your neck heal by improving circulation, maintaining flexibility, and easing muscle tension. However, since you’re currently in pain, you’ll want to stick to very gentle exercises initially. Always do these in a pain-free range – they should not sharply increase your pain. It’s wise to consult a physiotherapist who can tailor a program to you, but here are a few commonly recommended gentle exercises for cervical spine recovery:

Neck Retraction (“Chin Tucks”): This is a subtle exercise to strengthen the deep neck stabilizer muscles. Sit or stand with good posture. Gently draw your head straight back, as if you’re making a “double chin.” (Your chin tips down slightly and your ears move back over your shoulders.) Hold for 5 seconds, then relax. This shouldn’t be painful – you should feel a mild stretch at the back of your neck. Repeat 5–10 times. Chin tucks help correct forward-head posture and take pressure off the nerves.

Neck Range of Motion (Pain-Free Arc): Slowly and gently move your neck through comfortable ranges:

Rotation: Turn your head to the right as if looking over your shoulder (only as far as comfortable), then to the left. Go slow and avoid any grimace of pain. Maybe aim for 5 gentle turns each side.

Side Tilts: Tilt your head toward your right shoulder (bringing your ear toward shoulder) to stretch the left side of your neck, then tilt toward the left shoulder to stretch the right side. Only go until you feel a light stretch, not pain.

Flexion/Extension (with caution): Gently nod your head forward (chin toward chest) to stretch the back of your neck. Be cautious with extension (looking up); you can do a slight look upward if it doesn’t hurt, but since looking up aggravates you, it may be best to skip extension for now or do it only under professional guidance.

These movements help prevent stiffness. Think of them more as slow stretches rather than vigorous exercises. Do them perhaps 2–3 times a day, in a warm environment (after a shower or using a heat pack, muscles move easier).

Shoulder Blade Squeezes: Often with neck issues, the upper back muscles (between the shoulder blades) are weak or tight. Stand or sit up straight. Gently squeeze your shoulder blades together and down (as if you’re trying to tuck them into your back pockets). Hold 5 seconds, then release. Repeat 10 times. This opens your chest, improves posture, and can reduce neck strain.

Pendulum Arm Swings (for shoulder relief): If your shoulder is feeling tight or sore, bend at the waist and let your arm on the painful side dangle toward the floor. Gently sway your body so that the arm swings in small circles or back-and-forth like a pendulum. This can help traction the shoulder and neck slightly and relieve tension. Do for 30 seconds to a minute, a few times a day. It’s gentle and gravity assisted.

Nerve Glide Exercise: Sometimes therapists teach “nerve glides” for the arm nerves. A simple one (the “median nerve glide”): Stand with arms by your sides. Slowly straighten your affected arm and gently stretch it out to the side, with palm facing up, then extend your wrist (point fingers toward floor) – you may feel a mild tingling stretch in your arm. Don’t push into intense pain or tingling, just a mild stretch. This can help the nerve move more freely. But only do this under guidance if recommended, because if done incorrectly it can aggravate the nerve. I mention it because it’s commonly given for cervical radiculopathy but definitely get a physio to demonstrate first.

Important: All exercises should be confirmed with a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist before you fully incorporate them. I’ve listed typical gentle moves, but your healthcare provider can ensure you’re doing them correctly and safely. The timing of when to start these exercises matters too – you might need a few days of rest before starting, or you might start very light exercises immediately, depending on pain. A physio will guide you on this. They may also do hands-on treatments like gentle traction (where they lightly pull on the neck to open those foramina and relieve the nerve) or other pain-relief modalities.

As you improve, the physio will likely add more strengthening exercises for your neck and shoulder, and more stretches as needed. Eventually, you might do exercises with a resistance band for your neck or upper back, but that would be later when pain has subsided.

The key exercise principle now is “easy does it, but do something.” You don’t want to keep the neck completely still for too long (that can lead to more stiffness), but you also don’t want to strain it. Gentle, frequent movement in a pain-free range is ideal.

Finally, let’s clarify what a CT scan is (since you had one) and whether an MRI might be needed in your case, as that’s a common question.

What is a CT Scan, and How Does it Compare to an MRI?

You underwent a CT scan (Computed Tomography) of your cervical spine. Understanding this test can help clarify what it showed and why sometimes doctors order MRI afterward or not.

How a CT Scan Works: A CT scan is essentially a specialized X-ray machine that takes many images from different angles and uses a computer to create cross-sectional pictures (“slices”) of your body. For your neck, it produced detailed images of the bones (vertebrae) and some view of the disks and soft tissue. CT scans are excellent for seeing bone. They show bone spurs, fractures, and alignment very clearly. CT can also show gross details of discs and the spaces where nerves travel, but it’s still limited in showing soft tissues compared to MRI. CT scans involve ionizing radiation (X-rays) to create the image, but for a one-time scan the radiation dose is kept within safe diagnostic ranges. The scan itself is quick – usually just a few minutes – and you lie in a doughnut-shaped machine. In your case, the CT confirmed no fractures and identified the bony changes (spurs) causing narrowing.

How an MRI Works: MRI stands for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Unlike CT, it does not use X-rays; instead, it uses a strong magnet and radiofrequency waves. This technique is slower (taking 15-30 minutes typically) and you lie in a tunnel-like machine. MRI is excellent for visualizing soft tissues – things like the discs, spinal cord, nerves, and ligaments are seen in high detail hopkinsmedicine.orghopkinsmedicine.org. MRI can show if a disc is herniated (and by how much), whether a nerve is compressed or inflamed, and if the spinal cord is being pressed. It gives a more nuanced picture of the nerves than CT does josephspine.comhopkinsmedicine.org. However, MRI is not as necessary for looking at bone detail (CT already did that). Also, some people cannot have MRIs (for example, if they have a pacemaker or certain metal implants) because of the magnetic field hopkinsmedicine.org. MRIs are also more expensive and not always immediately available in emergency settings.

CT vs. MRI for your situation: In cases of trauma or acute injury (like your waterfall incident), doctors often start with a CT scan to quickly check for fractures or dislocations. It’s fast and great for emergency evaluation of bones hopkinsmedicine.org. Once a fracture is ruled out (as in your case), the next question is: do we need an MRI? An MRI would show more detail of the nerves and discs. For example, it could confirm how much the C5-6 disc is pressing on the nerve and if there’s any disc material compressing the spinal cord. Given your symptoms of nerve pain, an MRI could be helpful if:

Your symptoms do not start improving with conservative treatment over the next several weeks.

There is concern about something not explained by the CT (for instance, if you had significant muscle weakness or if we suspected a large disc herniation compressing the cord).

You were considering more invasive treatments like injections or surgery – an MRI would guide those interventions by giving a surgeon a detailed roadmap of the soft tissue.

In your case, the CT has already shown the likely pain generator (the moderate foraminal stenosis at C5-6). An MRI might show a bit more detail (perhaps the disc bulge contacting the nerve), but it probably wouldn’t change the initial treatment plan (which is conservative management). So, many doctors would initially treat you based on the CT results and clinical exam. If you improve as expected, you might not need an MRI at all.

However, if you find that after, say, 6–8 weeks, you’re not improving or if any symptoms worsen, your doctor may order an MRI to get a full picture of the discs and nerves josephspine.com. MRI would be the next step to rule out any surprises (like a fragment of disc pushing more on the nerve than thought) or if they want to double-check the spinal cord. It’s something to discuss with your doctor if you’re not progressing, or even earlier if you’re very curious about the soft tissue detail. But keep in mind, MRI is often a bit overkill early on if the management won’t change – it’s a fantastic diagnostic tool, just not always necessary if we already know the likely cause and are treating it.

Summary of CT vs MRI: Think of CT as a high-definition X-ray that’s great for bones and quick answers, whereas MRI is a detailed scan for soft tissues like nerves, without radiation, but it’s slower and costlier. In spine issues, MRI is gold-standard for evaluating nerve compression and disc issues josephspine.comhopkinsmedicine.org, while CT is often used for initial assessment of bones or if MRI isn’t accessible hopkinsmedicine.orghopkinsmedicine.org. You’ve done the CT; an MRI is a possible future consideration but may not be needed if you recover well with the current plan.

If you have questions about getting an MRI, bring it up with your healthcare provider. Given your moderate findings, they might say to hold off unless necessary. Many people recover fully without ever needing the MRI. If you did get one, it would just give a more complete picture (for example, confirming that the C5-6 disc is indeed impinging the C6 nerve root, and checking if the disc has any soft protrusion not visible on CT).

One more note: sometimes people ask if they should have the MRI in case something was “missed” on CT. CT is quite reliable for what it’s intended (bones and obvious large disc osteophytes). It likely did not miss any major issue, especially since your symptoms align well with what the CT showed. So, rest assured that we’re not in the dark – we have a solid understanding of your neck’s condition from the CT. MRI would just be for finer details if needed.

Glossary of Technical Terms

To ensure everything is crystal clear, here’s a glossary of the technical terms used in your report and this explanation:

Cervical Spine (C1–C7): The neck portion of your spine, consisting of 7 vertebrae (bones) numbered C1 through C7. C1 is at the top, just below the skull, and C7 is at the bottom of the neck. These vertebrae support the head and protect the spinal cord in the neck.

Vertebra (plural: Vertebrae): An individual bone of the spine. In your case, we talk about cervical vertebrae (the bones in the neck). They stack on top of each other and are separated by discs.

Intervertebral Disc: A cushion or shock-absorbing pad between each pair of vertebrae. It has a soft, jelly-like centre and a tougher outer ring. Discs allow flexibility of the spine and absorb impact. (In your findings, some discs have bulged a bit.)

Disc Osteophyte Complex: A combination of a disc bulge and an osteophyte (bone spur) that often occur together in degenerative spine changes. “Complex” just means the bulging disc and spur are seen as one combined structure pressing into an area. In simpler terms, it’s a bulging disc with some bony overgrowth attached.

Osteophyte: A bone spur – an outgrowth of bone that can form along joint edges due to arthritis or chronic stress. In the spine, osteophytes often form near the edges of vertebrae or where discs and bones meet, as part of spondylosis (degeneration).

Degenerative Changes / Spondylosis: Wear-and-tear changes in the spine, commonly due to aging. This includes disc dehydration or bulging, joint arthritis, and bone spur formation. “Cervical spondylosis” is essentially arthritis of the neck. Degenerative changes are usually chronic (develop over years).

Stenosis: An abnormal narrowing of a channel or opening. In the spine, it usually refers to narrowing of the spinal canal or the neural foramina. Stenosis can compress nerves or the spinal cord if severe. We classify it as mild, moderate, or severe based on how narrowed it is.

Central Canal Stenosis: Narrowing of the central spinal canal (where the spinal cord runs). Can potentially compress the spinal cord if severe.

Neural Foraminal Stenosis: Narrowing of the neural foramen, the hole on the side of the spine through which a nerve root exits. Foraminal stenosis can compress the nerve root (the part of the nerve as it branches off the spinal cord).

Foramen / Foramina: Latin for “hole” or “opening.” In the spine, foramina refer to the openings on the side between two vertebrae where the nerve roots exit the spinal canal. (Think of them as doorways for nerves.) Plural is “foramina,” singular “foramen.” Foraminal narrowing/stenosis means these doorways are partially closing in.

Nerve Root: The initial segment of a nerve as it branches off from the spinal cord and exits through a foramen. In the cervical spine, nerve roots are named for the vertebra below (except there’s a C8 nerve root even though there’s no C8 vertebra – a quirk of anatomy). For example, the nerve root that exits at C5-6 is the C6 nerve root. These roots then merge into peripheral nerves that go to the arms, shoulders, and so on.

Pinched Nerve (Radiculopathy): Lay term for what happens when a nerve root is compressed or irritated, often by a bulging disc or bone spur. “Radiculopathy” is the medical term when that nerve compression causes symptoms like pain, numbness, or weakness along the path of the nerve. In your case, a pinched nerve in the neck (cervical radiculopathy) is causing pain radiating to your shoulder and head.

Compression: In this context, pressure on a structure. We talk about nerve compression (pressure on a nerve) or spinal cord compression. Compression can cause the function of that nerve tissue to be disturbed, leading to pain or other symptoms.

Spinal Cord: The main bundle of nerves running down the centre of the spine, carrying signals between your brain and body. In the neck, the spinal cord runs through the cervical vertebrae. Compression of the spinal cord is more serious (can affect many functions below that level). Your scan shows no spinal cord compression.

Facet Joints: Small joints at the back of the spine where each vertebra meets the one above and below. They help guide the spine’s movements. They can develop arthritis in degenerative conditions. (While not heavily mentioned in your report, they are part of degenerative changes.)

Caliber: Thickness or diameter. When the report says “spinal cord is normal in caliber,” it means the spinal cord is of normal thickness (no thinning from compression).

Prevertebral Soft Tissue: The tissues in front of the spine (like throat area soft tissues). Sometimes used to assess swelling or injury. No prevertebral soft tissue swelling means there’s no sign of trauma-related swelling in the neck’s front tissues.

CT Scan (Computed Tomography): A diagnostic imaging test using X-rays taken from many angles to produce cross-sectional images of the body. Excellent for visualizing bones. In your case, it provided a detailed look at your cervical vertebrae and any bone spurs or obvious disc bulges.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): An imaging test that uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce very detailed images of soft tissues (like the spinal cord, nerves, discs) as well as bones. It does not use radiation. An MRI of the cervical spine is great for seeing exactly how and where a nerve might be compressed, but it’s typically done if more information is needed beyond the CT.

Moderate/ Mild / Severe (in context of findings): These are qualitative grades the radiologist uses to describe how significant something is.

Mild means a small degree – likely not causing significant effects.

Moderate means a medium degree – could be causing some effect (symptoms likely).

Severe would mean a large degree – often correlating with significant symptoms or risk (not present in your case).

If there are any other terms from the report you’ve heard and are unsure about (for example, sometimes reports mention “uncovertebral joints” or other such terms), feel free to ask for clarification. The ones above are the main ones relevant to your CT findings.

In Conclusion:

You have a clear understanding now of your CT cervical spine findings from April 7, 2025. In summary, you sustained a neck injury without any fractures, but the scan revealed pre-existing age-related changes in your neck that likely got irritated. The most notable issue is a moderately pinched nerve on the right side at C5-6, which is causing your symptoms. The outlook is good: with time, rest, therapy, and good habits, you are likely to recover well. Be patient and kind to your neck during this healing period – avoid the motions that hurt, use good posture and support, and do gentle exercises as tolerated.

Keep a positive mindset: many people your age have similar scans, and most get better with conservative care. It’s great that you sought medical evaluation and now have the knowledge to manage it. Your healthcare team (doctor, physiotherapist, etc.) will guide you through the recovery. Always communicate with them about your progress or any concerns.

I hope this explanation helps you feel more at ease and informed. Remember, your body has a tremendous capacity to heal. With the right care and precautions, you should be on your way to feeling much better in the coming weeks. Take care of your neck!

End of Client Report

Using this new service…

If you are interested in this new service please email hart@hartgood.com, direct message or leave a comment. For a little while, if you sign up for a yearly paid subscription to this newsletter, you will be able to experience this service at no charge. We anticipate that this service will cost around $200-$300 AU which may include a short consultation to clarify what is needed etc.