Health Literacy and OsteoArthritis (OA)

Part 1 of a series on the importance and benefits of Health Literacy. Focus on Osteoarthritis (OA) as an example.

If you have Osteoarthritis (OA) or work with someone who has OA, please give helpful input below in the comments so we can share your experience so that others can benefit. This can include resources not listed here, interventions that have worked for you, clinics and surgeons that are good and help, and indications as to what hasn’t worked for you.

What is Health Literacy

How does it benefit me?

In brief, there are 3 main aspects to Health Literacy (HL)

Knowing what enhances and sustains optimal health, both physical and mental. Daily factors to nurture and be aware of including sleep, eating regime, body composition (muscle and body fat), mental & emotional wellbeing, movement/exercise/mobility, minimising stress and Self-Knowledge.

Knowing as much as possible about any chronic health conditions you may have. This may include acquiring skills to seek out information and if necessary have someone help you understand it. This includes understanding what is specific about your situation and health status so that you can effectively communicate that to friends, family and health professionals as and when needed. At times it is natural to feel scared, frustrated, sad and sometimes angry. Be aware of these feelings and get help and speak up if they start affecting your daily life.

Acquiring confidence and skills to effectively utilise and communicate your knowledge about your unique situation when you interface with the medical system and health professionals. You feel empowered by making sure YOU are getting the best possible outcomes for YOU. Don't hesitate to ask healthcare providers to clarify information or repeat instructions.

Health literacy (HL) has been widely acknowledged as a pivotal factor in public health. It encompasses the ability to seek, comprehend, and apply health-related information in everyday life. Beyond merely receiving information and scheduling appointments, HL involves empowering individuals to effectively utilise their knowledge.

For points 2 and 3 above, this can take some time and persistence and there are depths and details that are unique for every individual. Often though, small simple changes and adaptations and a little learning have great benefits and remarkable health outcomes.

Point 1 above is all about prevention and reversing bad habits - knowing what enhances and sustains my optimal health. Previous articles have already touched upon Part 1 and links to them are below. More articles are to come.

Dietary choices significantly impact individuals’ health outcomes. Among recognised healthy diets, the Mediterranean diet has garnered considerable attention in recent years. Adoption of the Mediterranean diet has been associated with numerous beneficial health outcomes, benefiting not only individuals but also entire families . This dietary pattern is characterized by daily consumption of fruits, olive oil, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains. Additionally, it includes intake of fish and if available clean and sustainable poultry. It typically involves limited consumption of red meat and processed foods.

From Health Literacy and Its Association with the Adoption of the Mediterranean Diet: A Cross-Sectional Study, Ana Duarte et al, 2024

Health Literacy and Osteoarthritis (OA) as an example of a common chronic health condition.

In this article we will focus on parts 2 and 3 of Health Literacy as outlined above - knowing as much as possible about any chronic health conditions you may have AND acquiring confidence and skills to effectively utilise your knowledge.

Knowing as much as possible and keeping abreast about a chronic health condition involves several parts -

What is it, what are the symptoms, how long will I have it and is it reversible or curable

How did I get it

What are non- pharmacological interventions and preventatives to help manage and alleviate symptoms. These can include physical therapy and enhancing or tweaking sleep, eating regime, body composition, movement/exercise/mobility, minimising stress and Self-Knowledge.

What are pharmacological interventions and the range of different medications. What are the associated side effects and how do I talk to my GP about symptoms associated with medication use. How long do I need to be on a medication and can the dose be reduced or the medication stopped down the track, especially if symptoms improve due to increased non- pharmacological interventions and preventatives. What is the required schedule and routine required for taking the medication.

What are surgical interventions and the range of different options and the associated risks

Monitoring and Ongoing Education - keeping your own written record of medication schedule, supplement schedule, exercise/movement routine, weight, dietary changes, stress reduction & meditation/mindfulness AND your ongoing symptoms. It will also behoove you to get and keep your ongoing blood test results for yourself when you see your GP. These are useful to enhance and empower your knowledge whenever you speak with your GP or specialist.

It’s not rocket science and easily understood especially when a health coach or nutritionist etc explains it to you. You also save valuable time and stress if you have your results/records with you whenever you see another GP, specialist or allied health professional. The current medical system/model is such that GPs and specialists have very limited time with you, so being informed, preemptive and confident during a consult can enhance long term health outcomes.Support and Help and where to get it. This may be from organisations and bodies that specialise in a condition - like Osteoarthritis. May be from user groups and forums where individuals share knowledge and resources. May be from online sites if they are trusted sources and you have some research skills or are in the process of acquiring some. Maybe from coaches and allied health professionals. Or subscribing to trusted email sources that keep you abreast of new developments relevant to your condition.

Enhancing health literacy empowers people with a condition like OA to take control and manage their condition, leading to better health outcomes and quality of life. Health literacy is a continuous process that requires commitment from both patients and healthcare providers to ensure effective OA management.

1. Osteoarthritis - What is it?

What are the symptoms, how long will I have it and is it reversible or curable

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a condition that affects the whole joint including bone, cartilage, ligaments and muscles. Although often described as ‘wear and tear’, OA is now thought to be the result of a joint working extra hard to repair itself.

Common features of Osteoarthritis include:

inflammation of the tissue around a joint

damage to joint cartilage - this is the protective cushion on the ends of your bones which allows a joint to move smoothly. OA is characterised by the breakdown of cartilage, leading to pain, stiffness, and decreased mobility

bony spurs growing around the edge of a joint

deterioration of ligaments (the tough bands that hold your joint together) and tendons (cords that attach muscles to bones).

Osteoarthritis can affect any joint but occurs most often in the knees, hips, finger joints and big toe.

Osteoarthritis can develop at any age but tends to be more common in people aged over 40 years or those who have had joint injuries.

According to many authorities, there is no cure for OA. YET!

Remember - Daily factors to nurture and be aware of including sleep, eating regime, movement/exercise/mobility, minimising stress and Self-Knowledge can lead to more effective self-management that can also reduce symptoms.

From ARTHRITIS INFORMATION SHEET

Difference Between Osteoarthritis and Arthritis

1. Arthritis

Definition: Arthritis is a general term that refers to inflammation of the joints. It encompasses over 100 different types of joint diseases and conditions.

Symptoms: Common symptoms include joint pain, swelling, stiffness, and reduced range of motion.

2. Osteoarthritis (OA):

Definition: Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis and it primarily affects the cartilage, which is the smooth, slippery tissue covering the ends of bones in joints.

Symptoms:

Joint pain and tenderness

Stiffness, especially after periods of inactivity

Loss of flexibility

Grating sensation or bone spurs

3. Other Types of Arthritis:

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA):

Definition: An autoimmune disorder where the immune system mistakenly attacks the synovium (lining of the membranes that surround the joints).

Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA):

Definition: An inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis, a skin condition characterised by red, scaly patches.

Gout:

Definition: A type of arthritis caused by the accumulation of Urate (Uric acid) crystals in the joints, leading to sudden and severe pain attacks.

See more later in this article.

Understanding these differences is crucial for proper diagnosis and treatment, ensuring that you receive the most effective care for your specific type of arthritis.

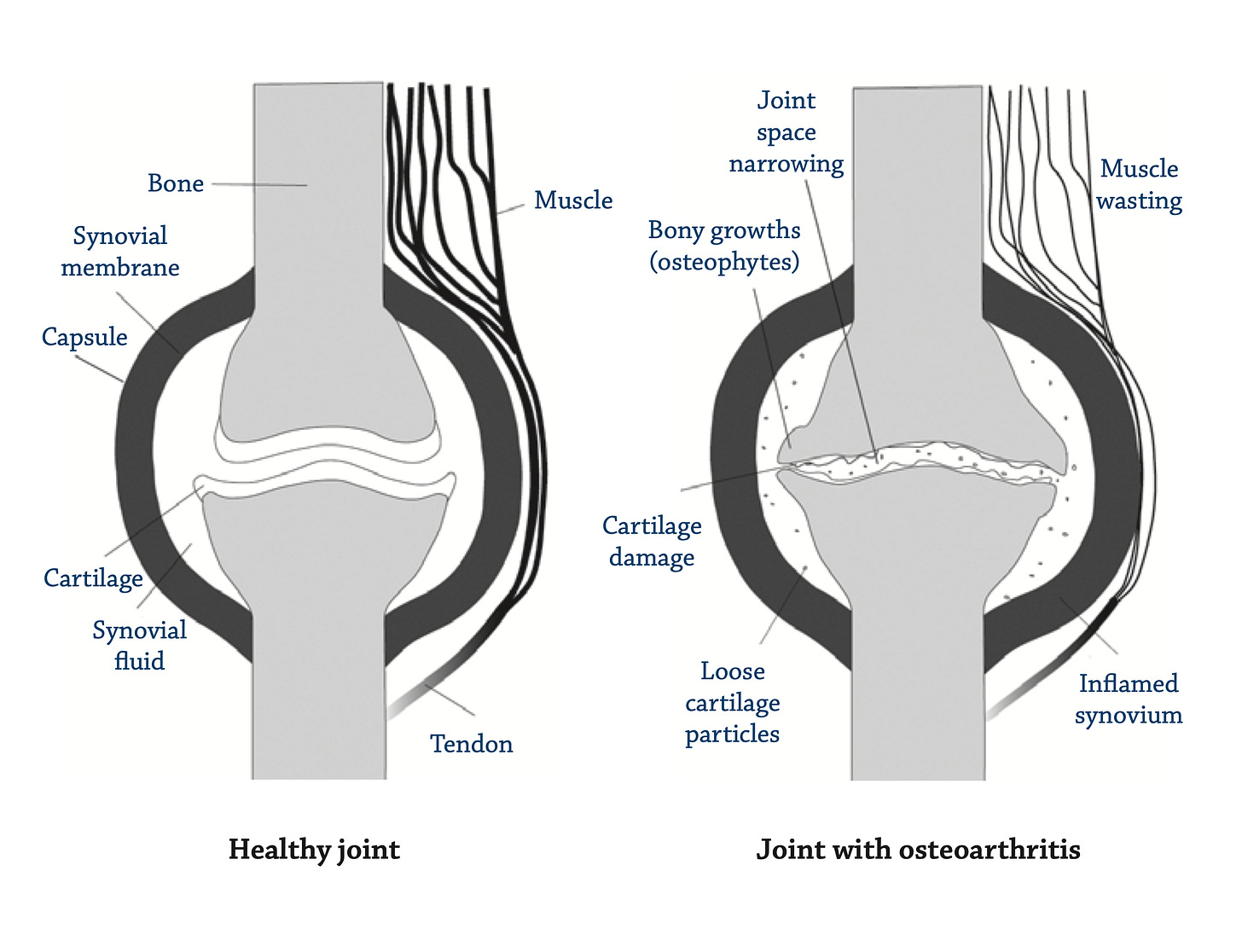

A healthy joint versus Osteoarthritis joint

Joints that are moveable are the ones that allow movement and flexibility of the body and these joints can develop OA.

The movement of joints is controlled by muscles that attach to the bone through tendons - see image above. The ends of the bones within a joint are covered by a hard, smooth tissue called cartilage. Its main functions are to reduce friction in the joints and to absorb the shock of movement. The cavity of the joint is filled with a thick fluid called synovial fluid. This fluid acts to lubricate the joint and prevent friction. It is made by the synovium, a tissue that surrounds the joint. The joint is stabilised by the tough outer part of the synovium known as the capsule and also by the surrounding muscles and ligaments.

In OA, changes in and around the joint are partly the result of the inflammatory process and partly your body’s attempt to repair the damage. In many cases, the repairs are quite successful and the changes inside the joint don’t cause much pain or permanent damage. Or if there is pain, it’s mild and may come and go. However, in some cases the repair doesn’t work as well and can cause longer-lasting changes in the way the joint feels, moves and looks.

From A picture of osteoarthritis in Australia, Australian Government, 2007

2. How did I get it?

We don’t fully know yet for sure, but a few theories exist. A range of factors, also called, risk factors, contribute to the onset and progression of OA. Some risk factors increase the risk of disease by affecting the mechanics (load, wear and tear) of the joint. Risk factors include: being female, joint misalignment, joint injury or trauma, excess weight, repetitive joint-loading tasks and genetic factors like family history. Factors that accelerate cartilage loss are described as risk factors for OA. Several biological factors associated with cartilage repair also increase the risk. Many of the factors act through a variety of mechanisms. More research is needed to determine exactly how these factors contribute to the development of OA.

Cartilage tissue needs to be continuously repaired and maintained. This involves a continuous cycle where old components are broken down as they age and new components are incorporated to replace those lost.

With ageing, the production of new components and the breakdown of old components becomes out of balance, leading to a net loss of healthy cartilage tissue. The imbalance in cartilage repair causes the cartilage to lose its elasticity and become more susceptible to damage. Over time the cartilage degrades to a point that it becomes rough and can split, break off or break down and expose the bone underneath. This process occurs gradually over many years.

Cartilage loss can be accelerated or slowed by mechanical, biochemical and genetic factors.

See more at - A picture of osteoarthritis in Australia, Australian Government, 2007

And - Living with arthritis Osteoarthritis of the knee

3. Non- pharmacological interventions

OA can lead to psychological distress and poor quality of life. All the non- pharmacological interventions have the ability to alleviate symptoms and improve psychological distress and quality of life, especially if you can incorporate all of them. May take some time and patience, but it is really worth it. Of course all these interventions will help with any other concurrent health issues you may have. And all the non-pharmacological interventions will help and enhance any of the pharmacological and/or surgical interventions.

As mentioned the non- pharmacological interventions include physical therapy, enhancing or tweaking sleep, optimising eating regime, body composition (reducing excess weight and supporting muscle mass), movement/exercise/mobility without causing ongoing damage to the body and joints, minimising stress and Self-Knowledge. Of course all these considerations will also serve to help prevent or minimise OA onset in the first place.

You may need the help of a nutritionist or health coach or community support group or class to effectively implement any or all of these interventions. See - Ongoing education and help at end for more local details.

4. Pharmacological interventions

An integral part of Health Literacy is to understand the options, side effects and toxicities of any medications you may take or currently take. This involves having regular conversations (once per year at least) with your GP/Specialist as to what is involved. The article below gives clear guidelines of what is important to consider when taking a medical drug along with the topics you can regularly discuss with the GP/Specialist.

Additionally, you can look up the medication details including methods of action and side effects on the consumer and health professional site - DRUGS.com One can search the medication by both brand name and/or the main active ingredient. It is global but still relevant for Australia.

The pharmaceutical management of osteoarthritis is a constantly evolving field. A narrative review written in 2023 looks at the current state of pharmaceutical treatment recommendations for the management of osteoarthritis.

This review was drafted to describe treatment guidelines, mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity for nine classes of pharmaceuticals:

1) oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

2) topical NSAIDs,

3) COX-2 inhibitors,

4) duloxetine,

5) intra-articular corticosteroids,

6) intra-articular hyaluronic acid,

7) acetaminophen(paracetamol),

8) tramadol, and

9) capsaicin.

In general, oral and topical NSAIDs, including COX-2 inhibitors, are strongly recommended first-line treatments for osteoarthritis due to their ability to improve pain and function but are associated with increased risks in patients with certain comorbidities (e.g., heightened cardiovascular risks). Intra-articular corticosteroid injections are generally recommended for osteoarthritis management and have relatively minor adverse effects. Other treatments, such as capsaicin, tramadol, and acetaminophen, are more controversial, and many updated guidelines offer differing recommendations.

From - Pharmaceutical treatment of osteoarthritis, M.J. Richard , J.B. Driban , T.E. McAlindon, 2023

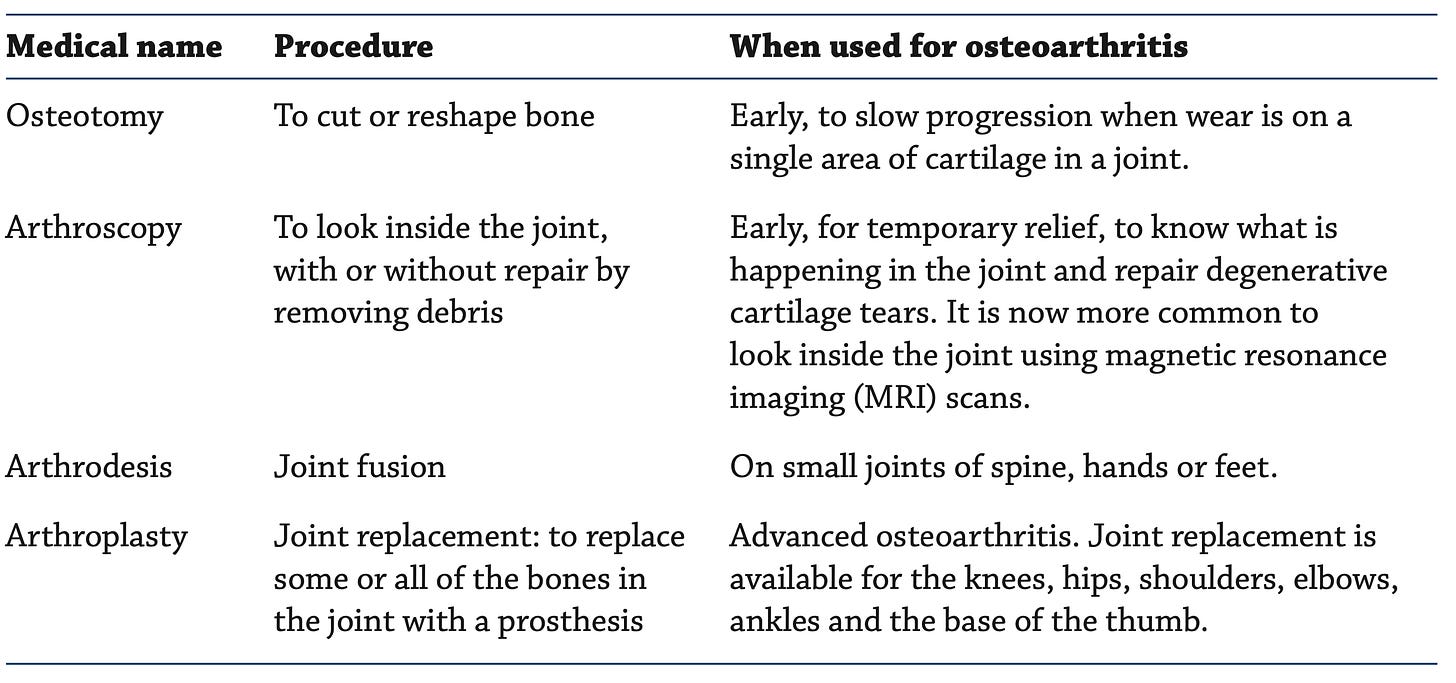

5. Surgical & other interventions

Example of common surgical procedure used for Osteoarthritis -

Note that new surgical procedures are constantly improving and becoming available. Ask around, ask your GP and do some research.

From - A picture of osteoarthritis in Australia, Australian Government, 2007

Example of Arthroplasty for Osteoarthritis

The images below are X-rays from my sister (permission given of course) of the results a recent arthroplasty operation for her diagnosed Osteoarthritis of the knee, that was progressive and painful. She is recovering well, although the surgeon has indicated that it can take up to a year to substantially recover, in part because the knee joint is very complex with bones, tendons, muscle, skin and nerves involved.

The images show new implants (bright white) of Titanium metal and other bonding material in the upper and lower knee bones along with an artificial patella (small round knee bone in front of the knee joint). The entire cartilage was also replaced (as it was almost absent) with a synthetic version - not visible on the X-ray as it is made from soft material so as to cushion the knee joint during movement, just like normal cartilage.

Arthroplasty is a common and effective surgical treatment for severe joint osteoarthritis and damage, providing significant pain relief and improved function, when other treatments have failed to provide relief. However, proper patient selection, surgical technique, and postoperative care are essential for successful outcomes.

What is Arthroplasty for Osteoarthritis (OA):

Indications for Arthroplasty in OA:

Severe pain that limits daily activities and quality of life.

Significant joint damage visible on X-rays or other imaging studies.

Failure of conservative treatments like medications, physical therapy, and lifestyle changes.

Types of Arthroplasty for Osteoarthritis:

Total Joint Replacement:

Knee Arthroplasty (Knee Replacement): Replaces the entire knee joint with metal and plastic components. It is indicated for severe knee OA that causes significant pain and functional impairment.

Hip Arthroplasty (Hip Replacement): Replaces the hip joint with a prosthesis made of metal, plastic, or ceramic components. It is indicated for severe hip OA.

Shoulder Arthroplasty (Shoulder Replacement): Involves replacing the shoulder joint with artificial components. It is less common than knee or hip replacements but indicated for severe shoulder OA.

Partial Joint Replacement:

Partial Knee Replacement: Only the damaged part of the knee joint is replaced, preserving healthy bone and cartilage. It is suitable for patients with OA confined to a specific compartment of the knee.

Hip Resurfacing: Involves capping the femoral head with a smooth metal covering instead of removing it. It is an option for younger, more active patients.

Surgical Procedure:

Preoperative Evaluation:

Comprehensive medical assessment.

Imaging studies to evaluate the extent of joint damage.

Discussions with the surgeon regarding the type of prosthesis and expected outcomes.

Surgery:

Performed under general or regional anesthesia.

An incision is made over the affected joint.

Damaged joint surfaces are removed and replaced with artificial components.

Components are fixed to the bone using cement or a press-fit technique.

Postoperative Care:

Pain management with medications.

Physical therapy to restore joint function and strength.

Gradual increase in activity levels.

Monitoring for complications such as infection, blood clots, or prosthesis issues.

Risks and Complications:

Infection

Blood clots

Prosthesis loosening or wear over time

Joint stiffness or instability

Nerve or blood vessel damage

Recovery and Rehabilitation:

Initial recovery includes hospital stay and intensive physical therapy.

Full recovery and return to normal activities can take several months to a year.

Long-term rehabilitation involves continued physical therapy and regular follow-up visits with the surgeon.

6. Monitoring and Management of OA

We don’t know as yet how to cure osteoarthritis, yet its impact can be reduced. Management of OA aims to control pain, reduce the load on the affected joint(s), improve or maintain mobility of the joints, and increase or maintain the strength of the muscles around the joint. This helps to minimise disability and improve the quality of life. Management involves several strategies, which work together to help meet these aims. Management of OA needs to be individualised to account for illness severity and the presence of other conditions. This includes mechanical aids and the medical and non-pharmacological interventions as mentioned above.

Effective management of OA is a team effort, involving the person with OA, their family, carers, the GP, coaches, specialists and allied health professionals. And ongoing self-care Education to develop Health Literacy is key.

And as mentioned, education can be provided by GPs, specialists, Nutritionists and health coaches, other health professionals, community groups, the Internet and pamphlets. A variety of programs and courses are available for promoting self- management in people with OA. These are often offered by Arthritis Australia (through their state and territory offices) or by community health centres.

If you live in Tasmania, Australia, have been diagnosed with Osteoarthritis and are a member of St Lukes Health Insurance, then a OA Pilot Program (2024) is available for FREE that offers regular physical movement/exercise classes AND additional one-one phone coaching with a qualified nutritionist (myself). This pilot program is facilitated by Health Business in Tasmania. For inquires use the Healthy Business contact form (quick response)or phone main office on 1300 655 530

7. Ongoing education and help and where to get it.

If you have OA or work with someone who has OA, please give helpful input below in the comments so we can share your experience so that others can benefit. This can include resources not listed here, interventions that have worked, clinics and surgeons that are good and help, and warnings as to what hasn’t worked for you.

8. Information Sheets

From - Arthritis Australia

Other types of arthritis

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

A form of Arthritis of unknown origin that affects young people.

Multicultural Arthritis Information Sheets

If you require any of these information sheets in a language other than English, please visit Arthritis Australia at https://arthritisaustralia.com.au/get-support/resources/information-sheets/. Information sheets are available in the following languages: Arabic, Chinese, Croation, Greek, Italian, Korean, Macedonian, Persian, Spanish, Vietnamese - from Arthritis & Osteoporosis Tasmania

9. Recent Research on OA

- will be updated periodically

“Alterations in gait mechanics and neuromuscular function have been linked to the initiation and progression of knee OA. The loading response phase, which immediately follows the initial contact of the heel with the ground, induces an abrupt, large loading impact on the lower limb joints. During this critical phase, the quadriceps muscle functions eccentrically to control knee flexion excursion and thus attenuate the impact of knee loading. Reduced quadriceps strength and increased co-contraction of muscles spanning the knee joint have been studied and shown to be significant predictors of the onset and progression of knee OA. Conceptually, passive muscular tension may also influence knee flexion excursion and dynamic joint stiffness and thus may increase the risk of knee OA.

Quadriceps weakness is a known risk factor for the onset of knee osteoarthritis (OA). In addition to muscle weakness, increased passive stiffness of the quadriceps may affect knee biomechanics and hence contribute to the pathogenesis of knee OA. Interventions for reducing the passive stiffness of the quadriceps should be included in preventative training programs for older adults.” Passive stiffness of the quadriceps predicts the incidence of clinical knee osteoarthritis in twelve months, Zongpan LI et al, 2023

“Our findings are encouraging, because they show that some women who are diagnosed with OA make changes in line with those suggested in the clinical guidelines for non-surgical management of hip and knee OA, established by The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), the OA Research Society International (OARSI) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). The strongest evidence based non-pharmacological management recommendations include weight reduction and land based exercise. In our study, approximately 67% of the women with OA were overweight or obese, and of these, about one in six lost weight following OA diagnosis (compared with one in ten in the No OA group). This is important, because obesity is a major risk factor for the onset and progression of OA. and weight gain is associated with an increase in arthritis symptoms, while weight loss is associated with a reduction in symptoms. It is important that practitioners continue to encourage overweight patients with OA to lose 10% or more of body weight, as there is a dose–response relationship between weight loss and pain and functional status.” Lifestyle behaviour changes associated with osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study, Norman Ng et al, 2024 - An Australian Study

“This review proposed practical recommendations on physical activity and the Mediterranean Diet (MD) in the elderly. It very specifically presented safe and effective exercises that will contribute to healthier aging. In this respect, the Mediterranean Diet (MD) has demonstrated to be superior to other diets with regard to preventing and managing common chronic diseases in aged patients.” Mediterranean Diet and Physical Activity for Successful Aging: An Update for Nutritionists and Endocrinologists, Evelyn Frias-Toral et al, 2022

“Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a progressive and multifactorial disease that leads to joint pain, muscle weakness, physical disability, and decreased quality of life. In KOA, the quantity of hyaluronic acid (HA) and the molecular weight (MW) are decreased, leading to joint pain due to increased wear of the knee articular cartilage. Our results showed that a single intra-articular injection of HA significantly reduces pain and improves joint function at four weeks.” The Effectiveness of a Single Hyaluronic Acid Injection in Improving Symptoms and Muscular Strength in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Multicenter, Retrospective Study, Domiziano Tarantino et al, 2024

“The pathogenesis of OA is complex, involving a variety of genetic, lifestyle, and other factors, and is not fully understood. Certain lifestyle and health factors are found to be definitive risk factors for OA, such as excessive physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Current studies have outlined a role of diet on OA progression. This study aims to explore the association between specific food items, including coffee, tea, fruits, dairies, meats, vegetables, and nuts, and osteoarthritis using genetic data from the UK Biobank. Interestingly, our findings identified four dietary preferences which may impact OA, namely coffee, peas, watercress, and cheese, where the first two had a promoting effect and the last two an inhibiting effect.” The role of dietary preferences in osteoarthritis: a Mendelian randomization study using genome-wide association analysis data from the UK Biobank, Long Chen et al, 2024

The pathogenesis of OA involves the interplay between mechanical and biological processes, including inflammatory and metabolic factors that create an imbalance between joint damage and repair. Indeed, synovial joints are considered an organ with their own physiology and OA can affect multiple joint structures, including its muscles, nerves, synovium, capsule, ligaments, menisci, subchondral bone, as well as the articular/hyaline cartilage. Core recommendations repeatedly emphasise the importance of diet and exercise therapy for individuals with knee OA. Exercise programs should be individualised. Exercise therapy that is structured, supervised, and group-based may optimise adherence. Fundamentals of osteoarthritis. Rehabilitation: Exercise, diet, biomechanics, and physical therapist-delivered interventions, Kendal A. Marriott and Trevor B. Birmingham, 2023

Cartilage is solely composed of cells known as chondrocytes. Chondrocytes maintain the extracellular matrix (ECM) and produce the cartilage matrix. Surrounded by collagenous fibers, chondrocytes release substances to make cartilage strong yet flexible. “This study provided insight into how chondrocytes can undergo various metabolic changes during OA. These changes include mitochondrial dysfunction and a shift towards glycolysis, which are related to chondrocyte catabolism and cartilage deterioration… metabolic alterations are essential to the etiology of OA. Targeting these metabolic changes may offer new alternative options for OA treatment.” A very in-depth review article doing deep dives in biochemistry and physiology of OA. The metabolic characteristics and changes of chondrocytes in vivo and in vitro in osteoarthritis, Miradj Siddick Adam et al, 2024

“Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a common disease, which is often with local pain, joint deformity, swelling and motor dysfunction. In the late stage of KOA, it would greatly reduce the quality of life. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an effective method for treating end-stage knee joint disease. With considerable progress in medical technology, TKA is widely used. Owing to extensive soft tissue dissection, osteotomy, and other surgical interventions during TKA, blood loss, pain, swelling, and poor functional rehabilitation remain important factors hindering efficient rehabilitation in TKA. Some studies have reported that cryotherapy applied to soft tissue injuries successfully reduces early local limb pain, swelling, and the inflammatory response, and promotes early rehabilitation during TKA.” Cyclic cryotherapy with vitamin D facilitates early rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty, Fulin Li et al, 2024

Osteoarthritis (OA) affects 240 million people globally. Few studies have examined the links between osteoarthritis and the Mediterranean diet (MD). The aim of this paper was to systematically review and analyze the epidemiological evidence in humans on the MD and its association with OA. … These studies described a positive association between a higher adherence to a MD and the quality of life of participants suffering OA. The prevalence of OA was lower in participants with a higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet. Biomarkers of inflammation and cartilage degradation related to OA were also analyzed and significant differences were detected only for IL1-α, which decreased in the MD group. Osteoarthritis and the Mediterranean Diet: A Systematic Review, 2018

If you live in Tasmania, Australia, have been diagnosed with Osteoarthritis and are a member of St Lukes Health Insurance, then a OA Pilot Program (2024) is available for FREE that offers regular physical movement/exercise classes AND additional one-one phone coaching with a qualified nutritionist (myself). This pilot program is facilitated by Health Business in Tasmania. For inquires use the Healthy Business contact form (quick response)or phone main office on 1300 655 530